From the Archives: Throwing Rice

[In the late 1990s, just back from working at the Moscow Times, I lived in Los Angeles, writing, finishing my MFA, and working as everything from an editor of drivers-ed textbooks to a Santa Monica Mountains dog walker. I was getting used to a new way of being in the world—and of being back in my own country—and I loved to wander the many worlds encompassed in those two strange and lovely letters, “L.A.” This peculiar little matrimonial Halloween tale appeared in the 1999 edition of the Southern California Anthology.]

[In the late 1990s, just back from working at the Moscow Times, I lived in Los Angeles, writing, finishing my MFA, and working as everything from an editor of drivers-ed textbooks to a Santa Monica Mountains dog walker. I was getting used to a new way of being in the world—and of being back in my own country—and I loved to wander the many worlds encompassed in those two strange and lovely letters, “L.A.” This peculiar little matrimonial Halloween tale appeared in the 1999 edition of the Southern California Anthology.]

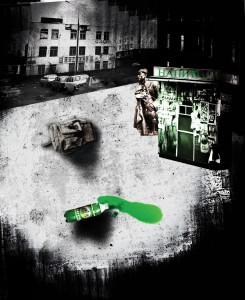

Illustration by Svetlana Larionova Miller.

Throwing Rice

West Hollywood, California, October 31, 199-…

The violinist played a sonata whose title we had already forgotten.

We listened, we spoke.

Avowed bachelors and bachelorettes received the tokens of their doom.

Family members and the friends of their friends asked us questions about money.

We danced to a song nobody else knew.

And they left.

And, walking through celebration’s ghostly afterglow, so did we.

Only the china remained, scraped-off cake frosting drying in gargoyle formations.

★

The city. On our own.

Cars lined up and sniffing at each other like unfixed dachshunds. Yapping and growling and making impact, but nobody’s getting any satisfaction tonight. Just be patient. Everyone wants to celebrate. Just be patient.

“It’s a vintage hotel.”

“Vintage?”

“Nineteen-twenty-something.”

“Oh, how nice.”

“That means no underground parking.”

“I’ll keep an eye out for a space.”

★

We got within two blocks. Nothing. We turned back. Twenty-three blocks from the Hotel Concordia we parallel parked, our Subaru’s tailpipe pointing the way to our honeymoon suite.

★

“Here comes the bride!”

They spoke simultaneously, two white-bearded young fellows in green three-piece suits, top-hats, and brass-buckle shoes.

“Are you gonna bring us luck?”

“You look great, honey! We almost wore that today!”

“Why, thank you,” she said.

★

With the rest, we flowed like plasma onto a main road.

Here car traffic was blocked off by striped sawhorses, orange cones, a vast array of silver and yellow reflectors, and a single burning flair.

“First night, baby!”

It was a mustachioed man in blue baby pajamas with booties and a hood.

“Yep.”

He took a long suck on his passifier.

“Mind if I join you?”

“Maybe the second night.”

“Aw, that’s no fun.”

★

A cheerleader hopped about not far in front of us, skirt flying up over smooth and muscular legs, short shirt lifting to reveal the tanned and toned contours of a lower back.

The cheerleader turned around, spit out some cigar juice, wiped the ashes off his goatee and smiled at my wife.

“Hey, hun, that’s what I wore last year!”

“Where did you rent it?”

“Rent, hell! I get a lot of wear out of that little number!”

“I’d love to compare sometime.”

“Honey, I’ll be around. If you search, you shall find.”

He smiled and skipped away.

★

My wife smiled at me.

I remembered a certain day walking by the track, turning to see the trumpeters boogie in the distance while the Professor of Marchingbandology, apparently a member of the revolutionary Frente Marchingbandista, barked commands over a loudspeaker. The trumpeters kept playing the chorus of “Carry On Wayward Son” again and again, each time interrupted by the sandpaper yelp of the Professor, who appeared to be an exiled New York intellectual named Bernie. A comical and graceless scene.

Then in floats my ironic counterpoint, the love of my life, all tights and tanktop and tanned arms, twirling a baton, twirling herself, twirling my heart…

When she lifted her arms and the shirt rose with them I felt the curve of her side upon my cheek. I rose and rose toward the hourglass pinch, a fine golden cilia haze tickling my new-shaven skin.

I felt like a pervert and a stalker and a happy young man and I waited and we dated and now she is my wife.

★

Actually, that’s not how it happened at all, but that’s the memory of her my imagination drummed up after seeing the goateed, cigar-smoking cheerleader.

Not a bad memory, for a fake one.

★

But there is something real here, something real and beautiful, I told myself, remembering an overcoated February afternoon near lake Michigan when two faces wrapped in scarves somehow saw enough through the wool to agree to coffee. The image may not throb and burst for you. But for me…

When the feather of a frame of life brushes me just so….

I feel it in my teeth. That’s where I feel it. A tickle in the teeth.

And the tickle is only reflectively felt. I don’t feel it when I read the sentence, but when, having read it, remembered it, reread it and remembered it from another angle, after investing faith and patience in it, I don’t so much remember it as burn it into my genetic code. I feel the tickle when something dear finally becomes a part of me. The feather’s touch is delayed, like the echo from a deep canyon. But it is sweet.

And I felt it there, walking with my wife. She was golden in a white gown, the most beautiful vision in the…

But the featherframe tickling me was she in a heavy hood, her burgundy scarf hiding lips I had yet to see.

★

I like the nightlife/ I like to boogie/ On the disocoayaiii!!!

I think it was Donna Summer who walked by us with a ghettoblaster, but I can’t be sure. Perhaps it was Dionne Warwick.

Anyway, she stopped and said Mazeltov.

We looked almost like the real thing, she added.

★

The crowd grew too dense for conversation. There was a red devil with a calico cat on its shoulder. There were any number of Elvises, one of them in a pink leotard. There was a blue Martian (“No, dammit, I’m Venutian”) with a giant papier mache erection that he kept pulling off and happily waving around. At the end of it was a white flag with the words “I surrender” written in laundry marker.

I tried to keep my eyes on the hotel in the distance, but three Sitting Bulls in pastel headdresses found their way in front of me. From then on I was the Miata behind the Mayflower truck, trusting those mightier than me to indicate the redlights and the greens and the exits off the freeway. I’m not that tall anyway, so it was just a matter of time, headresses or no….

★

A lad with a shaved head tripped over his jackboots and fell hard into my side. Instinctively I put out my hand to help him up. He sneered at me and I almost threw him back down. Then he smiled quickly and said with a gingerly lisp, “I’m not a Nazi but I play one on TV.”

“And you play it well.”

“Speaking of playing well, you two don’t look bad yourselves!”

“Well, we study the parts.”

“Oh, that Strasberg stuff just drives me crazy. I can never fully relax.”

“Yeah, that’s always tough.”

“As a matter of fact… Yes, I see it, just barely, but I see it. You’re not fully relaxed. You’re still playing the role. You have to be it.”

“We’ll work on it.”

“Oh, she’s doing fine. It’s you that’s got the tension thing going…. Wups, there’s my gang!”

He gestured to a pair of pretend skinheads to his right.

“I hope everybody gets your irony.”

“Oh, who cares.”

“Well, you’re pretty brave coming out here like that.”

“Oh, no, honey. You’re brave.”

And my new friend was gone.

★

“My feet are killing me!” she said.

“You’re tellin’ me!” called out a guy in stilettos and fishnet.

“We’ll get there soon.”

“How do you know?”

“It was straight ahead. If we just keep going, we’ll get there.”

“I’m just gonna collapse to sleep.”

“We’ll get there.”

★

If you take a rain check on your first night, is the second night your first night? Or is there only one first night, a single pitch down the middle, to be hit or missed but never to be seen again. Is there ever another such pitch? If you miss the first night, or foul it off, do you just swing wildly for the rest of your life, hoping for that grapefruit you can nail, hoping and hoping as Cupid the peashooter keeps flingin’ ’em up there for you to foul into the dugout or pound into the dirt. Do you swing wildly? Or do you play it disciplined, have a good eye, plan the romance, meticulously re-create that which was missed… Create just the right throb and doublethrob and unforgettable explosion…

The crowd goes wild.

★

I forgot for a moment about the feather I’d already felt.

“Stay awake. We’ll get there.”

“So I can sleep?”

I stared at her.

She wasn’t smiling.

“We’ll get there.”

★

If you just take the pitch on the first night, are you really married? What makes you married? Bowties and lace and little plastic people planted in lemon spongecake? Your lasting love, which pre-existed and will post-exist the masquerade? Or is it the overall transformative portrait of that day, the throb, the reality so sharp that it burns in right at that moment, not later in review, but right at that moment, a legend simultaneously lived and recited, a painting whose greatness is assured even as the artist lashes at a half-empty canvas…

★

Someone belched in my ear.

Someone elbowed my wife.

Someone stepped on the heel of my shoe.

★

I wanted my legend. I didn’t want subtlety, irony, comedy. I wanted my legend. I wanted my throb.

My wife was falling asleep on my arm.

★

“Hey, look honey! It’s another pair of newlyweds!”

The voice rang out from several feet away. We felt the plasma around us rearrange itself as a pair of plastic people flowed toward us. It was a nice looking fellow and a lovely blonde bride who could have been us if they weren’t just playing at it…

“Wow,” said the fellow, now alongside me. “You guys even have that exhausted look! Don’t they look like the real thing, honey?”

“Oh, dear,” she said, addressing my wife, “pardon my husband we’ve just had a real wedding today. We didn’t expect to get caught in this! You two do look good, though.”

“Thank you,” my wife said sleepily.

“We’ve got a honeymoon suite at the hotel up ahead,” the man said. “I hope we get there before the little lady here conks out on me.”

“Don’t bet on it,” said the little lady.

“Aw, hell, they’re always down just when you get up,” said the man, his voice all bubbly and weightless.

“Actually,” I said, “We really do have to get to the hotel. We really did get married today. And our wedding night really is getting fucked up.”

“Hey there, don’t get sore,” said the man. “We didn’t steal your costume idea. We just picked a weird day to get married, I guess. Suppose we should’ve left tonight to the pretenders.”

“We’re not pretenders.”

“Sure you’re not.”

“You’re pretenders.”

“No, we’re the real thing.”

★

My wife’s head was on my shoulder, her eyes three-quarters shut. She breathed rhythmically, like a curled cat before the fireplace.

“These people take their dress-up games seriously!” the man was telling the woman.

We walked on, the four of us, to the hotel, where something would happen, or nothing at all.

The Set in the Woods

I stand on the edge of an artful world,

Where the red of the fire

Is dimmed by smoke.

Don’t be alarmed:

Everything is under control.

Only the eyes

Flash like traffic lights

Beneath the pale sunset moon

Of a temporary town

In a dried-grass clearing.

We have work to do:

“Quiet on the set!” they cry,

Out of pure habit—

Nobody is saying anything anyway;

Only nature speaks its night language.

They seem dissatisfied with the semi-silence,

But uninterested in its source.

Who wants to concede that the world goes on without us?

Even the wild dogs

And the dying leaves

And the face of a child in the forest

Go unnoticed, unheard, unseen, except by me,

Here on the edge, lost on the job

In the temporal space between last and next

And not-quite-now.

It’s never quite now with me.

I am not exceptional,

But somehow I am an exception,

Dazed by incomprehensible pauses in the action,

By my own elusiveness when community beckons.

I never knew life had such breaks.

I thought the story told itself, beginning to end,

In such a way that made it difficult for the characters to simply run off.

I wander into the woods, no purpose, no plan.

Like a hero from Cooper,

The child steps on a twig beneath dry leaves.

The twig—such lonely applause!—cracks;

From behind the cover

Of a lightning-struck stump,

A dog turns with a start,

A muffled growl, and then

A bark.

The child jumps,

The shimmer of surprise upon him like a feather on the soul.

Where had that dog been hiding?

And how did he get lost out here

Among the cedars?

The boy drops to his knees

And against my unspoken recommendation

Pets the lost mutt.

From the edge of the clearing

I smile to myself.

The kid is safe, I assume,

A local boy. I turn around

To those traffic-light eyes

Which now flash in the dark

As the director’s commands

Drown out the dog’s bark.

– Greg Blake Miller

Outside Golitsyno, Russia, 1993

Six years ago, those of us who had studied Russian and East European history and culture already understood that the emerging conflict between Russia and Ukraine would shake the world, but we could not have predicted the strange ways in which its tremors have rattled internal politics across Europe, North America and beyond. In early 2014, Ukraine, placed once again on the balance beam between East and West, deposed its leader and attempted a westward tilt. Russia responded swiftly, exploiting Ukraine’s cultural rifts and historical peculiarities to annex Crimea and stoke a civil war in eastern Ukraine. Western sanctions followed, which were in turn followed by an

Six years ago, those of us who had studied Russian and East European history and culture already understood that the emerging conflict between Russia and Ukraine would shake the world, but we could not have predicted the strange ways in which its tremors have rattled internal politics across Europe, North America and beyond. In early 2014, Ukraine, placed once again on the balance beam between East and West, deposed its leader and attempted a westward tilt. Russia responded swiftly, exploiting Ukraine’s cultural rifts and historical peculiarities to annex Crimea and stoke a civil war in eastern Ukraine. Western sanctions followed, which were in turn followed by an