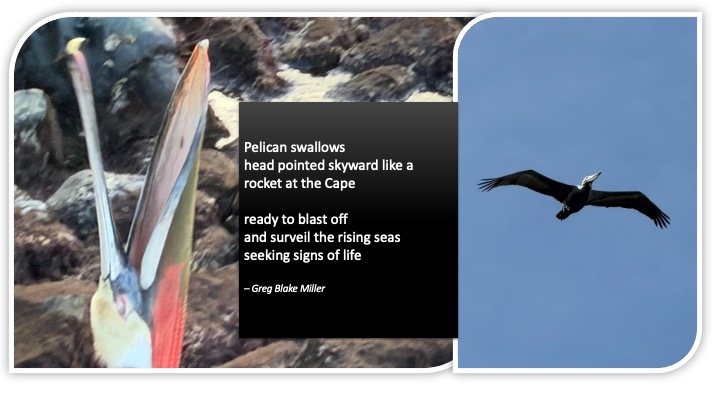

Pelican Refueling

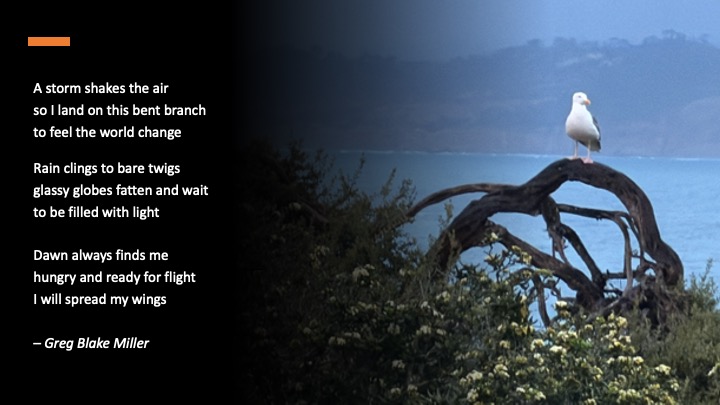

The Storm and After

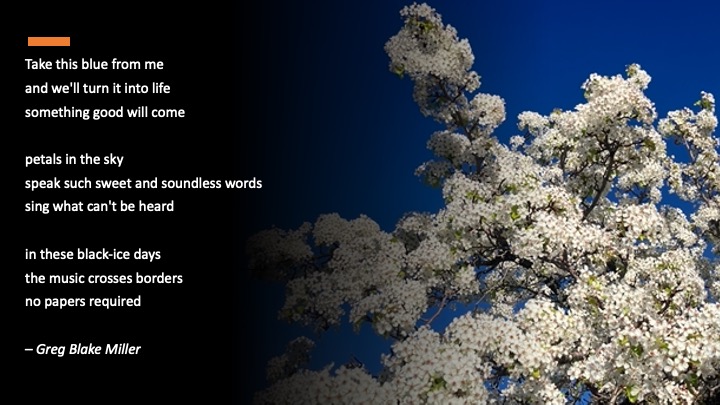

Ice and Incense

In the hammering snow and brutal ice they gathered to make their stand,

hoping to protect this street, these friends, this dream, this home, this land.

False warriors were all out in force in their fine play-acting garb;

state news rang out with lies and hate and snark and bile and barbs.

In some churches, pastors buried gospel and took Christ’s name in vain.

They had the choice to choose their way; they chose the path of Cain.

All through this land and many more, the holy Word is scorned

and used to load the guns of war, the lamb of peace now horned.

You can’t love your neighbor as yourself but tear her from her child,

can’t say you love the stranger then expel him to the wild,

can’t follow paths of incense when in truth they’re really smoke,

can’t claim you’re fixing anything when all the things you broke

lie in pieces in the streets and shattered on the plain

and you rage at every living soul that goes against the grain

and your concept of the sacred law is the one the tyrant winks,

the one he changes night and day and every time he blinks.

Devil, loose your arrows with blessings from your king;

the rich are lining up in droves just to kiss the ring,

but there’s one man in a ballcap, one woman in a car,

a million folks in waking dreams, one wish upon a star,

one storm of conscience in the head, one tightening of the heart,

one roiling sense deep in the gut that we should play our part.

It might be on this winter road or in the voting booth,

but time has come to pay our debt to the bank of truth.

I sense the people will not quit,

sweet madness in their hearts.

I don’t know how the protest ends

but this is how it starts.

– Greg Blake Miller, January 28, 2026

Illustration by GBM, 2020.

Take This Blue From Me

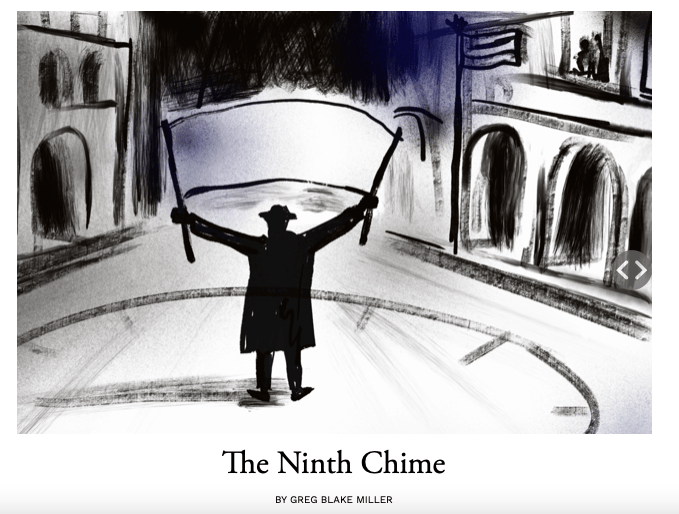

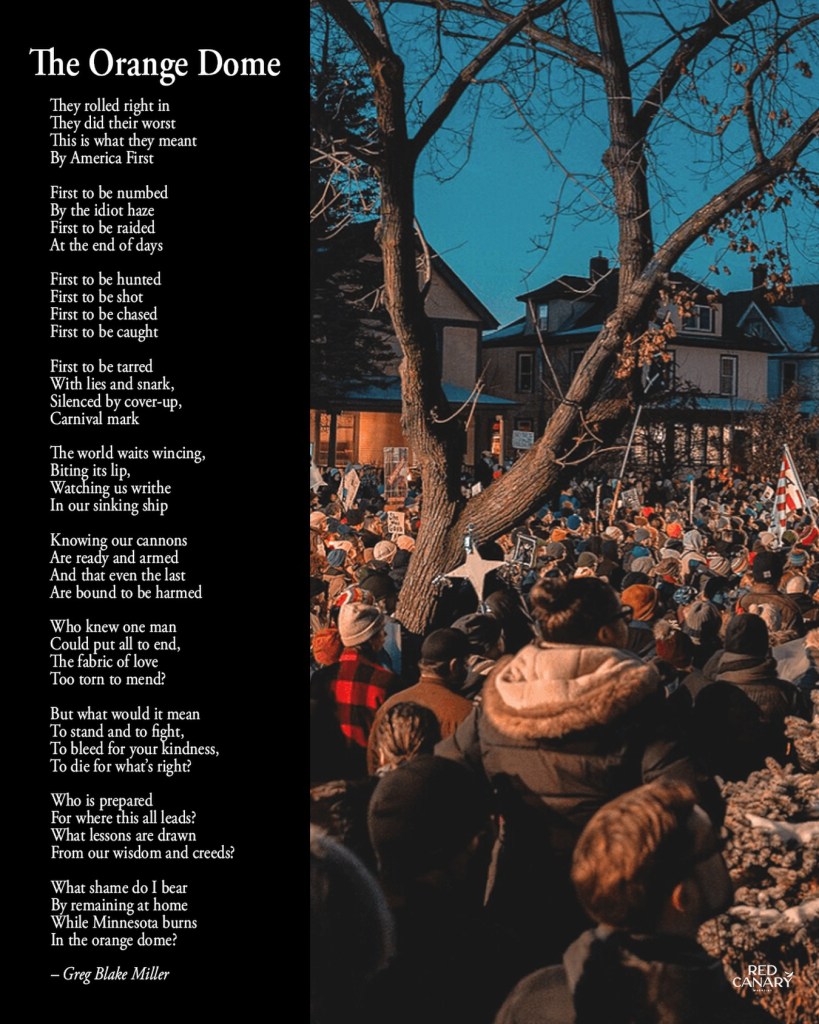

“The Orange Dome” in Red Canary Magazine

On January 24, as I watched the images of Minneapolis on TV while editing a book about a faraway but everpresent war, the drumbeat of a poem took shape. Many thanks to Joe Donnelly, Victoria O’Campo, and the team at Red Canary Magazine for creating this stirring graphic and publishing it in such a timely manner. (Photo by Chad Davis, Wikipedia Commons, for Red Canary) See the poem on the Red Canary site, along with other terrific RC offerings, here.

Greg Blake Miller discusses “The Kuleshov Effect” and more on the Ocean Bridge podcast

Last month, Ocean Bridge—a remarkable group of novelists, poets, journalists, publishers, editors and other creatives from Ukraine and the Russian and Ukrainian diaspora—invited Svetlana and me for an online “author’s evening” focused on my novel The Kuleshov Effect (Эффект Кулешова) and other projects I’ve got in the works. What a privilege and pleasure it was to spend a couple of hours on the “Bridge” speaking with and reading for these extraordinary people!

The recording of the session is now up on YouTube, complete with some old photos and even a song… The caveat is that most of it is in Russian, but I read in English at these spots: 18:24 (The first scene in “Kuleshov”), 43:23 (how the American student Tom Benjamin winds up with a litter of kittens in Saint Petersburg), 1:34:17 (where I actually sing Tom’s song for Kira), 1:39:30 (about Tom’s mind-bending journey to the symphony to listen to Shostakovich), and 2:19:56 (my recent poem, “Phantom”). For the Russian speakers out there, there’s lots of fun conversation and intel on how the book came to be, and Svetlana Miller reads several of the chapters in Russian, from Kira’s point of view.

Many thanks to everyone who attended, with a special hat tip to the poet and peerless captain of Ocean Bridge, Gari Lait (author of Confluences); editor extraordinaire Oleksiy Kretovich; the wonderful writers Marina Dyachenko (co-author, with Sergei Dyachenko, of the Vita Nostra series), Dmitry Bykov (Дмитрий Львович Быков, VZ: Volodymyr Zelenskyy and the Making of a Nation), and Alexei Nikitin (Victory Park); the scholar Victor Shtern; and the founder of Freedom Letters publishing, Georgy Urushadze (winner of the American Association of Publishers’ 2025 International Freedom to Publish Award)! #FreedomLetters #globusbooks

To watch this episode of “The Ocean Bridge,” please click the image above.

I hope to bring this book to an English-language readership soon!

A Diplomatic Epistle

Dear Homeowner,

In response to your grievance, initially filed 11 years ago and periodically amended, indicating that your neighbor broke into your home, killed several of your family members, moved into four of your rooms, and began raising your children, we have held substantive discussions with your neighbor and respectfully request that you officially cede the deed to said rooms, surrender the larger baseball bats with which you have been defending the remainder of your house, commit to the principle that, when under future attack, fewer of your family members will attempt to defend it, and withdraw your application to join the Neighborhood Watch. Please respond with your agreement by Thursday.

Respectfully,

The Association

VP:dt

On the Centenary of Marlen Khutsiev

I wrote this poem for one of my heroes, the great film director Marlen Khutsiev (1925-2019), way back in 2009. Today, he would have turned 100. I always wished I would have sent this to him when he was alive.

The Author, Open Source

To Marlen Khutsiev

You promised yourself to certain principles—

A probing awe of the present,

Humility before the past and future.

You promised yourself that when you turned your head,

Or craned your neck,

Or just held still,

You would try to see in things all that they give you to see,

Neither stopping at the surface

Nor injecting the image with alien fashion and fad

And making of it a symbol of something else,

Some popular present

Or politically preferable past.

You promised yourself to capture the image

In all its integrity,

To make its present into a past

And send it on

To those who would use it

In ways you would not have imagined.

It’s no small task to release the catalogue

Of one’s sight

To the busy minds

Of a new and otherly-comprehending generation.

But maybe, if you were there to see,

Their use of your awe

Would gladden your soul.

—Greg Blake Miller

Hagiography

Bones dry fast in Western dust

Gone two hours—erect the bust

Tears dry quick, resentment bleeds

Follow that trail where you want it to lead

Never miss a chance to use the dead

They always say just what you want to be said

From what crows pick clean, make a marionette:

Jaws speak with your voice

Jaws carry a threat

Alas poor Yorick,

Your stage awaits:

The gaze of the eternal

The grandest of fates.

We’ll weave what we can

From the clues of your life

We’ll salt the fields

We’ll seed the strife

And your sacrifice … to us …

Won’t be in vain

We’ll resurrect you

As an agent of pain

Good God, grant revenge, sweet stench

We’ll divine your will, we’ll dig the trench

Bring the last battle nigh; Gabriel, sound your horn

Let the enemy weep; let his locks be shorn

Seek not the truth; the truth speaks lies

The angel cries, the devil sighs

This is what it sounds like

When bones dry.

– GBM 9-11-25