Diplomacy’s Final Exam

Without a dose of humility, Russia and America will not pass the current test. And we’ll all pay the price.

By Greg Blake Miller

Note: I wrote this piece on January 20, 2022, looked at its bleak tone, and promptly filed it away, hoping the ensuing weeks would prove my pessimism wrong. So far, they haven’t. In fact, my thoughts at the time now seem to have been unduly optimistic. But I believe there are lessons, even at this late date, in looking at the larger context of the post-Cold War era to understand how we got here. Thus my decision to pull these pages off the shelf and post them on this cold 2-22-2022, when even the digits of the date look like soldiers on the march.

Russia is calmly knotting a noose for Ukraine. The United States is bandying about the airy concept that any nation that wants can pursue membership in NATO, which is purest nonsense because an open club is not a club at all. Meanwhile, Russia’s bid to negotiate begins with a set of non-negotiable demands, and the American counteroffer sees each of the Russian demands as a “non-starter.” All parties have led with the chin and left themselves with few ways to save face.

A friend wrote to me this morning asking me for a prediction. Knowing that I’d lived in Russia, worked for a Moscow newspaper, studied the country for many years, written a dissertation on Russian culture, and married a Russian, he leaped to the assumption that I might know what to do about Russia.

This is a question of Hegelian complexity, considering that even Russia does not know what to do about Russia, a subject on which Russian novelists have built lasting reputations.

But I love Russia in a love-your-wayward-brother way. And I love America in a love-your-wayward-self way. So I accepted my friend’s fool’s errand and tried to not only parse how we got here, but predict where we might be heading. It was fun to write and entirely disturbing to read. With that endorsement, read on, with the understanding that the sole purpose of predictions is to reveal our fundamental foolishness in the face of time and sloppy humanity.

The Almost-Doomsday Scenario

Tucked away in antiviral seclusion, Vladimir Putin may be trying to devise a way he can avoid the invasion and still declare victory, but his rhetoric has left him short on options. He could decide to take advantage of the opening President Biden gave him when, in his January 19 press conference, he appeared to signal that the U.S. considers a “minor incursion” on Ukrainian territory a pinkish, rather than red, line for NATO.

The Biden Administration swiftly walked back the supposed gaffe, but it wasn’t really a gaffe: It was a bit of nuanced truth-telling at a moment when such truth was entirely unnecessary. In the “minor incursion” scenario, Putin stages a provocation in Eastern Ukraine and starts an apparently “limited incursion” in the Donbass—territories over which he already has significant leverage and some loyalty among the primarily ethnic-Russian population. Such an incursion would split NATO (and President Biden has publicly state that NATO nations are indeed divided “on what they’re wiling to do”): Members would hesitate to commit resources and human lives to a part of Ukraine that many have already written off as a region that will be in “frozen conflict” for the foreseeable future. Having tested the West’s mettle in this way, Putin will then restate his demands while threatening a full-scale invasion of the remainder of Ukraine.

As at the outset of World War II, we have a side that has will but fewer long-term resources confronting a side that has less will but more long-term resources. In this equation, Russia would want to act swiftly, get what it can, and then negotiate from a position of greater strength. The West would possibly cut off Russia’s access to SWIFT, which controls global financial transactions (an extremely blunt instrument, in that it would cause a great deal of collateral suffering among everyday Russians), and provide arms to Ukraine for a massive and lasting resistance (both conventional and nonconventional). Russia would respond with massive cyberattacks on the West and possibly move its hypersonic missiles closer to the U.S.

The conflict in Ukraine itself may become a quagmire for Russians—even if they “win” swiftly by toppling the Ukrainian government and either annexing or installing a puppet, they would face a lasting and well-armed resistance. We could also expect, however, that a good deal of U.S. weapons technology would wind up either in Russian hands or in the hands of an emerging class of criminal warlords. The risk for all sides is an Afghanization of Ukraine.

The winner in all of this is China, which would delight in the damage to the West while supporting Russia just enough to turn it into a client state.

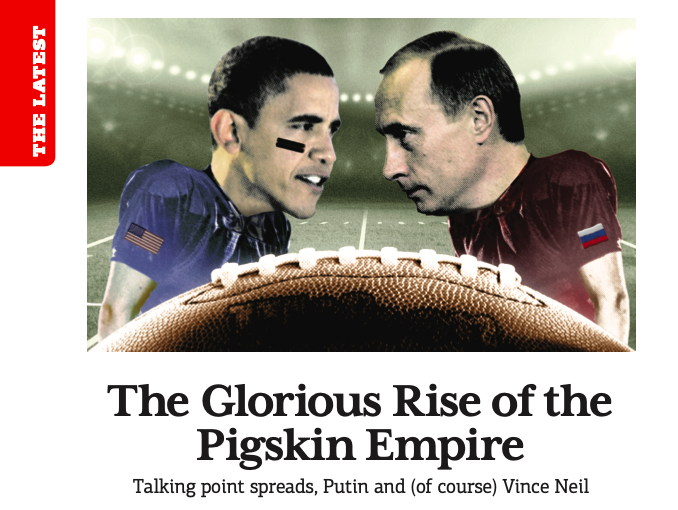

The Accursed Past, or The Wisdom of Monday-Morning Quarterbacking Was Readily Available on Sunday

First, let’s consider NATO’s Open Door policy, which the West uses to explain why committing to Ukraine’s non-membership is a “non-starter.” NATO justifies the policy by reference to Article 10 of the organization’s founding treaty. But Article 10 is not an open door policy. Here is the text:

The parties may, by unanimous agreement, invite any other European State in a position to further the principles of the treaty and to contribute to the security of the North Atlantic area to accede to this Treaty.

In other words, an invitation must be extended. Which in turn means NATO has the freedom not to extend an invitation. And this means that the West’s current rhetoric about the Open Door policy is both misleading and has been fecklessly used as a tool to back itself into a diplomatic corner, a process that has now been unfolding since 1994, when NATO signaled its desire for eastward expansion. At the time, Russia was deep in its own difficult struggle become more like its Western European neighbors—secure, prosperous, open—without losing its identity. But, after the American-Russian air-kisses of the early 1990s, the expansion plans signaled to Russians that the West had decided that Russia not only had been, but always would be, a rival to be contained. Perception matters: NATO began as an anti-Soviet alliance, and for Russians, the enlargement of the organization toward their borders seemed a clear signal that NATO was being transitioned into an anti-Russian alliance. The perception also handed a discursive hammer to the anti-Western forces in Russian society, one they have used craftily for a quarter of a century.

George F. Kennan, the greatest Russia expert ever in the employ of the United States, vehemently warned against NATO expansion in the 1990s and later wrote that it was “the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-Cold War era.” The problem was not in the understandable desire among the newly unfettered nations of Eastern Europe for a sense of belonging in the greater European community, with the economic and security advantages that implied, but in the failure of the West to understand that NATO was an incendiary vehicle for that belonging. It was a time for new conceptions of European security, with new acronyms, and ultimately a place for full Russian participation beyond its outsider status within NATO’s well-intentioned “Partnership for Peace.” But neither creativity nor optimism carried the day. Once set in motion, the momentum of expansion carried NATO ever closer to Russian borders. In 1999, NATO welcomed former Warsaw Pact countries Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic. In 2004, the membership of former Soviet Republics Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia brought the alliance to Russia’s western frontier.

With each step, the relationship between Russia and the West further soured and the nationalists, militarists, opportunists and mystics in the Russian camp gained power. For some in the West, this was proof of some kind of inevitable baked-in trait of Russian national identity. For others, it seemed like NATO expansion had not only helped scuttle a moment of relative hope for a new relationship with a new Russia, but also had created a monster. The Russian militarist-mystic wing is fueled by grievance; provided the thread of a humiliation narrative, they will weave it into a garish tapestry and sell it to the people, again and again.

In 2008, NATO declared that it “welcomed” Georgia and Ukraine’s “aspirations for membership,” a move that managed to paint a target on the backs of two countries that shared a border with Russia without providing any assurances of security. In other words, the move functioned primarily as a propaganda victory for Vladimir Putin in depicting a nefarious Western plot to encircle Russia—a victory he used in 2014 as he rode a wave of high approval ratings while lopping Crimea off of Ukraine and facilitating a not-so-frozen “frozen conflict” in eastern Ukraine.

Why was the proposed “open door” to Ukrainian membership so incendiary for Russia? To ask this question—and to propose an answer—is not to excuse Russia’s use and misuse of history as a hammer, particularly when Vladimir Putin is a known purveyor of historical funhouse mirrors. But if we are to understand the emotional and cultural (not to mention economic and geographical) levers of the current crisis, it worthwhile to acknowledge the unique relationship between Ukraine and Russia: Kiev, going back to the year 862, is the original seat of both Russian and Ukrainian history—histories bound together over more than a millennium. Russians have an unfortunate tendency to claim that they are the lone heir of Kievan Rus, a medieval brigadoon sundered by the Mogol invasions of 1223 and 1240—but what followed the invasions were centuries in which two distinct but kindred cultures gradually arose. In 1654, Ukraine became part of the Russian empire after Ukraine’s great national hero, Bogdan Khmelnitsky, appealed to Russia in an effort to fight off Poles and built an independent Ukraine. After World War I, Ukraine briefly declared independence but was ultimately swept up in the Russian Civil War, with its own Whites and Reds battling for the ideological future. But for the better part of 400 years, the borders between Russia and Ukraine have been porous, and never more so than in the Soviet period, where people moved for jobs or love or were simply transferred hither and thither by the authorities. Today, families have brothers and sisters and parents and cousins on both sides of the Ukrainian border. The degree of cultural, social, economic, familial, and even romantic entanglement between the two countries is not entirely unlike that between American states.

To understand the fraught nature of the proposed NATO expansion to Ukraine is simply to acknowledge the welter of entanglements as they exist in the real world. It is not in anyway to deny that Ukraine should retain its independence and its ability to choose its own form of government and its own friends. It has its own distinctive culture, its own unique history, and a clear lack of desire for a return to empire. The problem—certainly not the only one, but an important one—is the symbolic weight of NATO and the understandable Russian perception that Ukraine as a NATO member would turn into a militarized strategic bulwark against Russia. Most ordinary Russians—outside the government and a fanatical nationalist core one might best translate as “Trumpy”—are fine with Ukraine not being part of a Russian empire; they’re fine with it not being a puppet-ruled client state. What they’re not fine with is it joining what is appropriately perceived as an enemy military camp.

The bitter seed of NATO expansion is the father of Putinism in affairs both global and domestic (where Putin has, in generally cartoonish tones, justified virtually every move by referencing the threat of a culturally, economically, and militarily ravenous West). It is entirely unsurprising that it is the seed of the present conflict as well. From the moment of the Soviet Union’s dissolution, thinking people realized that Ukraine was potentially the most dangerous flashpoint, a profound temptation for Russian irredentists.

Beyond the cultural reasons for this temptation, there were the geographical oddities that emerged from centuries of empire and imperial happenstance: Crimea, for instance, was not historically part of Ukraine, but in 1954 Nikita Khrushchev transferred it from Russia as a symbolic gift for the 300th anniversary of Ukraine’s absorption into the Russian Empire. On December 25, 1991, it became for Russians a sort of accidental foreign territory. Yuri Luzhkov, who was Moscow’s powerful showman-mayor during the 1990s and early 2000s and had presidential ambitions, was not shy about his desire to see Crimea (and most pointedly the city of Sevastopol, home to the Black Sea Fleet) returned to Russia. So there has long been an urgent need for the West to work with Russia and Ukraine to craft structures to allay foreseeable future conflict. But now the conflict is here, and 25 years of NATO expansion toward to the heart of the old empire has not only failed to prevent these dangerous days, but helped light their fuse.

The Future, or Exam Day

It’s true that the threat of NATO expansion to Ukraine could be used as a bargaining chip: We won’t bring Ukraine into NATO if you … (insert hard bargain here). But the timing makes such negotiation extremely difficult: When Putin is holding a gun to Ukraine’s head, even reasonable compromises acquire the stink of treachery.

Putin would, therefore, need to provide the West a way to save face in the case of such an agreement. He’d have to go far beyond merely withdrawing forces and permanently guaranteeing Ukraine’s security. A new Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty would have to be negotiated (the original one, between Reagan and Gorbachev in Reykjavik, was the high point of Cold War diplomacy). Interference in Western politics via hacking and state disinformation campaigns would need to end, the Petersburg troll farm would need to be disbanded, cyberattacks on US infrastructure would need to end, and Russia would need to prosecute supposedly nonstate hackers sowing trouble in the West. (The West would need to give parallel assurances on hacking, etc.) All of these reforms would need to be subjected to verification process on both sides, a return to the “trust, but verify” maxims of the Reagan-Gorbachev eras. (The West could conceivably sweeten the deal by acknowledging a fait accompli and putting recognition of Russia’s annexation of Crimea on the table, but such a move, with its whiff of abandoned principle, should be held in check unless absolutely necessary to win vital concessions.)

Ukraine would have to be part of these negotiations, not just a pawn on the Great Power chessboard. Such negotiations could build a modicum of trust between Russia and the West, and possibly start to complicate Russia’s seeming decision to rush into the arms of the Chinese. It could also prepare the ground among the Russian people for greater comity between our countries in the post-Putin era by taking the teeth out of anti-American propaganda.

Alas, we’re in a period where all negotiation is dismissed as weakness and therefore the accumulated bargaining chips are rendered worthless. Every possible tradeoff is immediately greeted with the dread incantation, Neville Chamberlain!

That leaves the West with its current unattractive options:

• War (which could degenerate into WWIII—the reason the West has repeatedly said that direct military action is off the table)

• Support of insurgency (which could lead to the aforementioned Afghanization of Ukraine), and

• Asymmetrical cyber- and financial warfare (which could have extraordinary costs on all sides, with accelerated domestic division in the U.S. and the pauperization, embitterment, and perhaps lasting anti-Americanism of ordinary Russian people).

Some Americans may be betting on the destabilization of a Russia that, recognizing the chaos and the price of adventurism, turns its back on Putin and Putinism. But that’s a dangerous bet indeed, particularly when nuclear weapons are involved. If the US has learned anything in the past two decades, it should be that the destabilization of vast regions stirs up a sandstorm of unintended consequences.

In a world of non-negotiable demands, non-starters, and the perpetual need to save face at all costs, it’s time to reexamine the nature of our conflict, rethink our needs, embrace the possibilities of diplomatic creativity, and ask ourselves what courage really means. War is occasionally necessary and inevitable. Stupid war may be inevitable, but it is certainly not necessary. The current conflict is a test not only of our will, but of our intelligence. So before we turn in the Scantron, let’s check our work and make sure we’re all as smart as we think we are.

More on Russian history and the Ukraine conflict:

• “Russia, Ukraine, and the Battle of Yesterday”

• “Harvest of Grievance”

Greg Blake Miller is a former staff writer for The Moscow Times. He holds a doctorate in international communication from the University of Oregon and earned his master’s in Russian, East European and Central Asian Studies from the University of Washington’s Jackson School of International Studies. He is the director of Olympian Creative Consulting and teaches media studies at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

The Obelisk

I’ve arrived in order to leave. I’ve chosen this place so that I can soon no longer be here.

Having arrived, I understand that I will be remembered, vaguely and by few, for having been. This was not the point of my arrival. I am not concerned with your memory. Who else do you remember that has arrived and then departed? Did you consider their presence somehow remarkable? Why is my presence remarkable and not theirs? Have you thought about what this says about you?

Having resided, however briefly, among these stones, I will have been part of this landscape, a stone of a different sort, the kind that keeps time by the moment rather than the millennium. You seem to think I should have wanted more—indeed, you tried to make me more, with your memes and clever talks and attempts to unpack mysteries that are not in the least mysterious. Are you more shocked by the unfamiliarity of my appearance or by the fact that I demonstrated no interest whatsoever in being seen? Why are you talking about me? Why have you made my appearance a matter of your public performance?

I simply wanted to be here, to have been here, to have been, to be, to live, to leave, to be elsewhere and otherwise.

But I am intrigued. I am interested in you. Who are you?

Some of you may be thinking of me. Now you’ve gotten me thinking of you.

I had no intention of returning. You may have changed my mind.

– Greg Blake Miller

P.S. Motivations bob and weave and backflip and melt and recompose on their way to turning into stories or meditations or whatever you’d like to call what you’ve just read. In this case, it started with haunting images of the mysterious Utah Obelisk. For more on that, and hints to how it provoked my thoughts on solitude and being seen, isolation and acquaintance, fame and forgetting, see Robert Gehrke’s excellent Salt Lake Tribune story on the fate of the obelisk.

Brain Fog

When the legendary Green Bay quarterback,

Who is on the screen as I speak,

Becomes “that guy on the Packers,”

When one of my closest friends becomes

“The tall dude from the magazine,”

When my dog, at leash’s end,

Will respond neither to my son’s name nor my wife’s,

Because the dog has a name of her own,

I will begin to believe that things will never be the same.

What will that feel like

If I can’t remember how they were?

– Text and photo by Greg Blake Miller

The Voter

I wrote this song on election day, November 3, 2020, while the returns were still coming in. Earlier that day my 20-year-old son tested positive for Covid and now sat across the room from me in a mask and face-shield, breathless in more ways than one, as the man on the screen assembled his jigsaw of red and blue. The boy’s fever had hit 101; he was shivering but riveted by the story that—as we now know—was just beginning to unfold.

The Voter

I’m a character in your narrative

A player in your game

I’m a piece upon your chessboard

I’m the fan upon your flame

You built yourself a platform

You spoke loudly, you spoke long

You won yourself attention

You earned yourself this song

And when all the counting’s over

I’ll still be here in this town

You’ll define me and decry me

You will say I’ve let you down

I will call myself forgotten

Though I never have been known

Misremembered, misbegotten

When my soul was out on loan

And you up in your tower

Sitting on your golden chair

You will waver, you will wallow

You will call this world unfair

I am lonely, you’re surrounded

I am sick and you are well

But your dreams have been confounded

And I wish you well in hell.

Covid, Cake and Cadlewax: A Thank-You Note

Fifty-first birthday, 51 days after the coronavirus (anagram: carnivorous) started snacking on my cells, five straight days of feeling pretty decent. Sounds like time for a slice of cake, a word of thanks, and a wish for better days ahead—for all of us. So: a word and a wish to my wife and my son who, though they too were sick, were there for me through every anxious day; to my friends, ever relentless with their good wishes; to the doctors and nurses who saved my skin not once but twice. Those knights in pale PPE not only brought me through a six-day Covid-pneumonia sojourn at the hospital but also through a post-Thanksgiving return trip to the ER, when the virus had hacked its way into my neurological and gastrointestinal systems and written an unpleasant code all its own. (I’ll leave it at that; this is a family show.) That second trip was, thankfully, not an overnight stay, but I was sent home with new meds and marching orders that got me through a bumpy fortnight, my own little Wimbledon with its own small victory. Five straight good days! What can you do but drop to your knees and look to the sky? You shake your opponent’s hand—“Well played, Covid.” Then you wash your hands, ready for whatever comes next.

Song of Life

The voices beyond the wall are young and full of today, nothing more: One has the ball, one wants the ball. Or maybe there is no ball; I can’t really hear what they’re saying, only their kid-tones through the yellow autumn air on Thanksgiving day, musical assurance that life goes on wherever it can.

Even I, a month into illness, five days from a hospital bed, feeling certain that my head will go on hovering like a helium balloon, have come out to play today, masked on the sidewalk, masked in the park, strolling past foliage gone impossibly gold, past a caterpillar finding its way across the sidewalk to reach a quiet place to reinvent itself, past a single curled red leaf collecting sunlight like cinnamon tea.

My wife is with me, my son, my dog. Only the dog has remained unscathed by this viral month, and a case could be made that she is leading us, she is keeping us whole in the world, she is requiring us to remain part of all that is. The voices of the neighborhood kids follow us home. During the early months of the pandemic, my wife whispered a sing-song sentence, “The birds don’t know, they sing and sing.” The kids are like birds, but they know. They know and they sing anyway.

Inspired, my son takes a tennis ball into the backyard, sets himself up before our old hoop, and commences an improvised version of basketball. He’s just turned 20; he’s home from college, part of the national effort to keep students away from the coronavirus. He got it anyway. After three weeks his lungs are once again growing strong with air, his muscles agitating for action. His gesture is open, the invitation is clear, Let’s play.

My mouth starts to say no, then I hear it say yes. Basketball leads to baseball catch, then to a specialized sort of catch where each of us are allowed to throw and catch only with our off-hands. My smart son tells me that this will foster new neural connections in my brain. Already the helium balloon is reconnecting with the body, already the world is calling me back, and wondering if I will accept the invitation.

Happy Thanksgiving.

The Roadside: A Covid Tale

My son, Elek, is the top-ranked compound junior male archer in the United States. Today he was supposed to be at the Gator Cup in Newberry, Florida, to cement that ranking for 2020 and earn his place on the junior national team. This had been his goal for six years, and he’d worked tirelessly to achieve it. This, as they say, was his moment. The tickets were purchased, the bags were packed. But last Sunday he developed a high fever, which shot up further on Monday. On Tuesday morning, Election Day, he tested positive for Covid-19. I can tell you that young people can, indeed, have heavy symptoms. Elek is still quite ill.

For seven months, we were extremely careful. Our corona-caution extended to a whole assembly-line ritual of “de-Coviding” the groceries when we brought them home. Elek is taking his classes online for his sophomore year at the University of Arizona. We wear our masks. We’ve tried to be true to the early social principles of the coronavirus era, when we were told that we were all in this together, before it became politically useful for powerful people to use the virus to tear us apart. Between March and October we traveled just once, to the USA Archery SoCal Showdown, where Elek won gold.

Two weeks ago, we decided to make a short trip to Tucson so that Elek could visit his university and spend some time working with his coach. He wanted to get his shot, his bow, and his mindset in top shape for Gator Cup, which would be the final tournament of his junior career. Again, we were cautious throughout the trip—masks, clean hands, giving others as wide a berth as we could in aisles and on paths. All the same, the journey felt like a sort of return to the wide world, a rediscovery of a lost planet. We brought our dog; we walked her on dusty trails among exotic cacti and tangled green mesquite; red-tailed hawks soared above, an owl hooted from someplace unseen, families of quail skittered through the brush. The dog is a border-collie-beagle, silky black on her back, wooly white at the chest, 11 years old; she’s had three surgeries in 11 months; two to remove tumors, one to fix hind legs that had worn themselves out. She seemed to get younger on these walks; her steps were swift, her eyes alight with nature, her nose reading the encyclopedia of a fresh new world. Her sense of health made us all feel healthy, the world cooling into bright autumn, all the year’s poison burned off at last. We have these sensations sometimes: pleasure, longing, hope, mirage.

***

Elek’s Tucson training lasts four days—he’s ready now; his bow tuned to sweet precision, his shot rhythmic and true. Time to head back to Las Vegas, stay healthy for a few more days, and head off to the big tournament. We drive the bright highway, past Picacho Peak, jutting into the sky like a cartoon cat, around the endless perimeter of Phoenix, weaving through Wickenburg. Political signs festoon even the smallest towns. We’d love to be listening to music, but instead we freight our journey with CNN.

Our dog needs to stretch her legs; we need a bite to eat. We pull off the road onto a gravel driveway where a corrugated-steel hangar houses our favorite little roadside cafe. The owner has become a friend over the years. She always greets us with kindness; she takes an interest in our lives, and we in hers. She makes wonderful pies. Elek goes in to order a sandwich. There is no better sandwich on the road from Tucson to Vegas; you take a Sharpy and a little laminated card and check the boxes of everything you want. My wife, Svetlana, treasures this place more for its grounds than for its grub. She and I stay outside; we walk the dog through a sweetly overgrown garden, up a little manmade hill with a tiny waterfall. A scarecrow is sitting on a bench. Everything speaks of care, refuge. By the side of the cafe, in the shadow of a tangled mesquite, Svetlana pours some water for the dog. I go inside and sit with Elek. He has taken a seat, his mask still on; he waits for his sandwich. It’s quiet, peaceful; we’re tired and this place promises replenishment. Inside, the owner is not wearing a mask, but the place is empty.

Several men enter the cafe, none of them in masks. They are talking loudly about constitutional originalism. One is wearing a red cap with a famous slogan; he says he’s been to a big political rally. Elek’s sandwich, which he had ordered to-go, arrives on a ceramic plate. He tries to eat quickly. Svetlana appears at the door with the dog; she waves to the owner, and the owner, kind as ever, smiles, gestures to our dog, whom she knows well from the passing years, and says, You can bring her in!

Now we are, all of us, sitting in the small cafe, a few feet from the unmasked men, listening to their latest jurisprudential theories. Svetlana orders a slice of pie to go and a cup of tea, but once again, the food, which is delightful, arrives on a ceramic plate, complete with a scoop of melting vanilla ice-cream. The owner asks my wife if she wants the pie warmed up. Caught in the spirit of the moment—we like the owner, she likes us, the food is good—Svetlana says yes. The men at the counter are talking more loudly; they know all the news, a certain sort of news. Elek has stopped eating his sandwich and put on his mask. We wait. A large family enters unmasked—a mother, an aunt perhaps, a couple of little kids, a teenage girl—and forms a chatty semicircle around the cash register.

We have, in six years of traveling to and from Arizona, never seen the place this crowded. We’re pleased that business is going well, and we really want to leave. It is an American scene, in some ways the best of America—people of all sorts interacting with a certain generosity, the kind that makes people open with their views and the stories of their daily lives. In ordinary times, it would feel healthy—the kind of social health the Internet has robbed us of. But these are not ordinary times, and the difference between goodness and, frankly, un-Christian indifference to others is as thin as a peace of simple cloth worn over the mouth and nose.

We ask for our food to be packed up. Svetlana and Elek head outside with the dog; I wait for the semicircle around the cash register to disperse so I can pay. The owner asks me about Elek’s archery, his school, how we’re holding up through the Covid era. I ask her about business, about her family. I can’t resist engaging in conversation; this sort of engagement is a relic of my earlier self, the one that lived before the pandemic, and I don’t want to let go of it.

We get back on the road, arrive home in the evening to catch the final innings of the World Series on TV. Our beloved Dodgers win for the first time in 32 years. One of the star players, Justin Turner, receives news of a positive Covid test in the eighth inning and has to leave the game. Later, he returns to the field to celebrate with his teammates. He pulls off his mask for the team photo; he lingers, exchanges hugs and high fives. We can’t really blame him, except we can. This season of American life allows no pure sensations of triumph.

A few days later, the first sign appears—Elek’s dream, in which a new species of tarantula-lizards are engaged in some kind of internecine war, attacking and devouring one another. A day after that he is sick, and a day after that the Covid diagnosis arrives. Now we are all wearing masks in the house; Elek doesn’t want to get us sick, so he even puts a shield over his mask; he looks like an astronaut, going through his days, taking his online tests, looking at his bag, still packed for Florida, sitting in the middle of the living room.

On the Thursday after Election Day, Svetlana and I develop fevers, too, along with coughs, body aches, shortness of breath and sharp sore throats. On Friday, we test positive as well. Last night was long and difficult for all of us. I woke in the deep of night, entirely unable to breath; I caught my breath and calmed myself by thinking about, of all things, writing. We each have our own peculiar coping mechanisms. With all due respect to the flu, which can be serious business, this is not just the flu.

***

I don’t know if we were infected that day at the cafe. I hope not; the place was a small grace note in our lives, and I don’t want the memory of it to be upended by this new meaning as the source of illness. I have always thought of the cafe as a place of refuge and solace on a long, desolate road. I’d like to keep thinking of it that way. Maybe the virus came to us by some other means, at some other place. But I can’t help thinking of the strange aggression that causes our fellow men and women, our brothers and sisters who know of the fragility of both their bodies and ours, no matter how mighty we think ourselves, to forget the duty of care we all owe one another. I can’t help thinking of the simple gesture of putting on that mask, which could be the difference between sickness and health, or even life and death, or at the very least, a dream achieved or a dream denied.

– Greg Blake Miller

Electoral Aftermath: Jubilation, Anxiety and the American Future

After so much mourning, jubilation in the streets of America.

The celebration is well and truly earned, for these have been punishing years for believers in any of the old Superman virtues—truth, justice, the American way, back when it went without saying that the American way implied truth and justice. They have been punishing years for believers in democracy, in civility, in conversation and cooperation. They have been punishing years for people who believed that the Civil War had been fought and won by the right side, that the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments were every bit as much a part of the constitution as the words penned in 1787, that the collapse of Reconstruction was a calamity or that the Civil Rights movement was a moral triumph, however incomplete.

It has been a punishing season for people who believed that the scientific method has worth, particularly when we are dealing with matters of science, that the health of our brothers and sisters is not disposable, that we owe one another a duty of care, that political discourse is not a bloodsport.

It could be argued that we have all been naive, and that the very traits we disdain in the passing era are now permanent fixtures in the American social genome, engineered into place by the wizards of the Internet, who told us we could have what we wanted, and we responded: “Conflict.”

That’s where our work begins: Can we learn to want something else? Can we learn to treasure concord rather than discord, the non-zero-sum game in which we give a little, get a little and realize that the giving and getting aren’t mutually negating but mutually reinforcing? Can we embrace a public life not based on the negation of the other? Can we rise above the infantile language of winners and losers, acknowledge that we are on the same team, and play hard together?

These are our tasks, and this is our time.