American Crossroads

At some point, when the embers cool on the street and the news channels move on from the 24/7 coast-to-coast feed, the image we’ll need to remember is the one that started it all—the murder of George Floyd.

We will need to memorialize Floyd not only with tears, but with policy. The policy must not end with a revision of police procedures; it must include a rethinking of the American community. We can no longer consign entire neighborhoods, regions, races to the American Upside-Down in which the achievement of some modicum of stability, peace, and security is the stuff of against-all-odds TV movies. We must at last acknowledge that access to quality housing, healthcare and education is not a privilege but a right—the place from which a healthy society is born.

Food, shelter, health and learning are the proverbial bootstraps by which we keep telling Americans to pull themselves up. An America that cannot or will not allocate the resources for these bootstraps and yet continues to call itself the land of opportunity is a nation in the killing grip of delusion. We have a choice before us: concerted, optimistic action or defeatist self-destruction.

How, exactly, will we choose to make America great?

– Greg Blake Miller

Turning Off My Phone at Midnight

Staggered and beaten by pixels,

I fade, float, try to sink into warm cavelike analog darkness,

Blue light swimming on the walls,

My eyelids invaded by the inhuman outer glow of information,

Endless, bottomless, underworld stuff

Devoid even of the spirit of Hades,

Immaterial material,

Materialism without material,

Nothing tactile to reform or remake or melt or beat into ploughshares,

Weapons of inner war now securely tucked inside my mind

To deny even the independence of my disobedient dreams,

The dreams of a beaten man,

A man beaten by the infinite contents of his own pocket.

– Greg Blake Miller

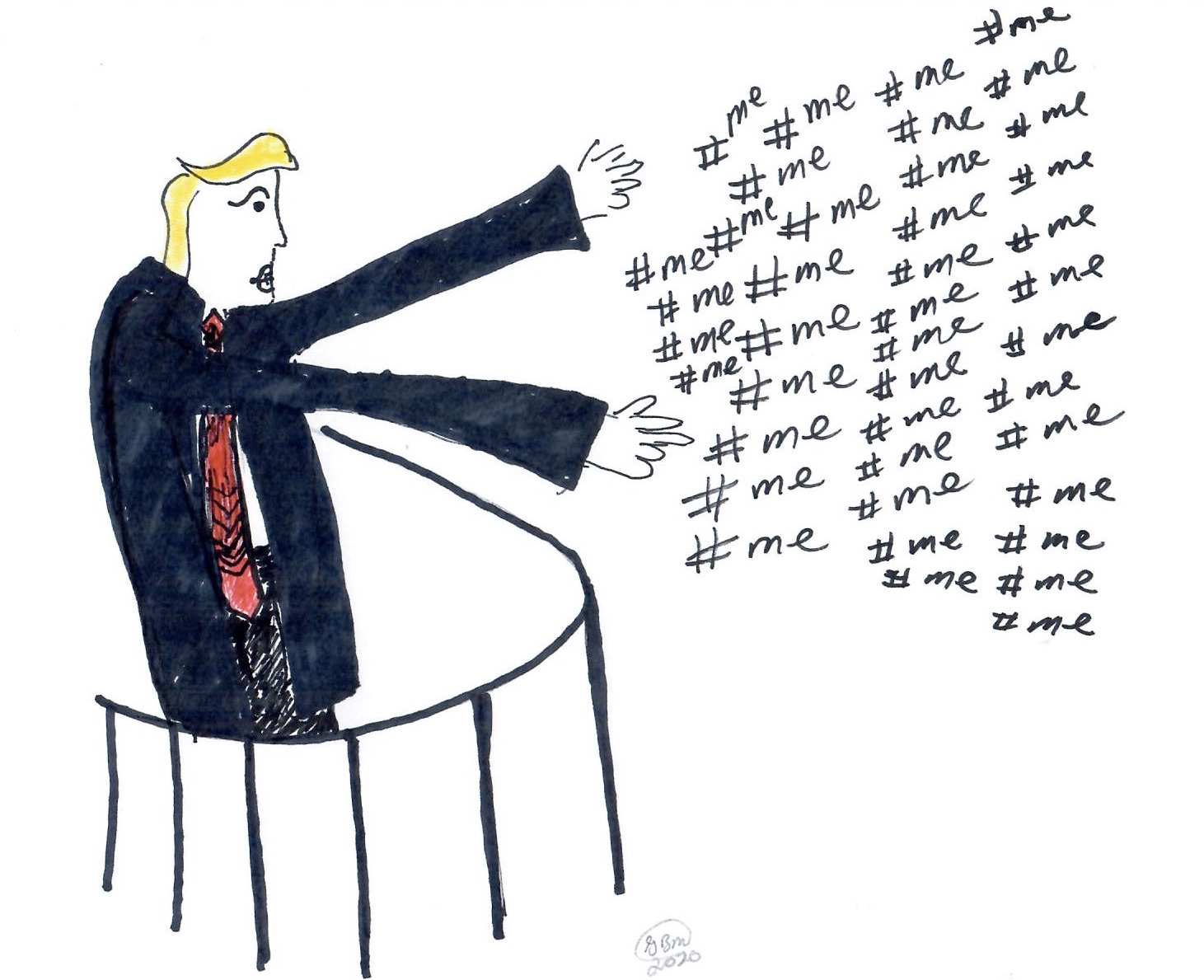

Authoritarianism Made Easy!

I know what you’re going through: You want to be an authoritarian, and it’s just taking too long. Here’s a secret: While you’re busy listening to the so-called “experts,” reading up on the Establishment’s “classics of authoritarianism” and deciding on your authoritarian “belief system,” others are cutting out the waste and actually being authoritarians. Think about it: You’re TRYING to be an authoritarian, while they’re actually living the authoritarian life. They’ve simplified their goals, clarified their message, and taken action on their dreams.

Well, now it makes sense to ask, “What do they know that I don’t?”

I’m here to help.

Today I’m going to let you in on what I’ve learned in decades of successful authoritarianism. Most aspiring authoritarians are wasting time and money on old-school “solutions” like authoritarian policymaking and crafting coherent authoritarian ideologies. With my simple seven-step program, you’ll learn secrets that can save you valuable energy that would be better used on the things you really want to do, like attacking enemies and watching television. These techniques have been used by successful authoritarians the world over. Don’t take it from me, take it from the well-known dictator Josef Stalin, who used these techniques in such brilliant managerial moves as The Campaign Against Trotskyites and The Denunciation of Rootless Cosmopolitans.

The simple tools I’m going to teach you work whether you consider yourself “right” or “left” or even simply “wrong.” True authoritarians know that these directional signals are window-dressing, the result of years of squandered energy in pursuit of old, tired ideas such as “justifying my draconian actions” and “building a seemingly coherent intellectual rationale for a crackdown.” If you’ve been spinning your wheels on such projects, you know that the only “right” is “I’m right” and the only “left” is “You’ve been left behind.” Don’t miss the opportunity to learn our PowerOfPower7™ Secrets today. No less an authority than the renowned authoritarian Adolf Hitler agreed with Stalin on these seven simple steps—and those guys couldn’t agree on anything. Well, there was that once, but we’ll blame that on Molotov and Ribbentrop.

This is the beginning of a journey that will allow you to overcome your inhibitions, silence your rivals, and bend the arc of history whichever way you damn well please. Why wait? Let’s get to the first Seven Steps!

Authoritarianism Made Easy, Lesson One:

Ridding Yourself of Rivals: Setting up Scapegoats in the Power Structure

- Assert authority. | You alone can fix it!

- Delegate authority. | Work smarter, not harder!

- Renounce responsibility. | It’s not your fault!

- Denounce those to whom you’ve delegated. | It’s their fault.

- Inflame the people against rival power bases. | Leverage the power of blame!

- Assert authority. | You alone can fix it.

- Purge rival power bases. | Winning.

With these simple steps, you’ll be dispatching enemies within days. Don’t waste time taking responsibility when you can be taking power! By putting these lessons to use today, you’ll take your first step* toward The Power of Power™ and impact countless lives in your community, or what’s left of it.

*Just for you we have a very special offer available today only: Write to us with your name, e-mail address, and checking account number, we’ll send you, at no cost, Lesson 2: Becoming Your Own Public Disinformation Officer.

– Text and illustration by Greg Blake Miller

There Will Be No Game Today

The spring of 2020

Is the player to be named later,

Left out of the headlines,

Which promised a bargain

For our side.

But these stories

Were based on insufficient data.

The reporting was incomplete,

Whether out of laziness

Or simple humanity:

Who knew?

Who knew that

When the deal was completed

It would turn out

That the Other Side

Had gotten everything.

– Greg Blake Miller

The Escape

They seemed so sure just who I was

And just where the winds would take me

And just what I dreamed when I slept alone

Beneath the willow tree

And that the blossom in a young girl’s eyes

Like a gypsy dream revealed tomorrow

And even the streetcorner saints

Wished me well on the path

I was sure to follow.

And they cleared the road

And swept the dust

But it clouded my vision

And I just saw hands

Grabbing, taking, giving with strings

Dreaming their dreams

In my unsure skin.

On desire’s rickshaw I rattled ahead

Upon their gladly burdened shoulders

And the city of gold glistened before me

And I glimpsed the crown that I would wear

And I turned with a start and tumbled out

And scraped my knee on sandy ground

And wound my way through crowded streets

And disappeared among the unknowns

And at the end of the path, the place I sought:

Before me, green grass, and a place called home.

– Greg Blake Miller, July 23, 1993

Kobe

Woke up this morning

And, fuck, it’s still true.

In the country of basketball,

Where my soul spent its youth:

All of the flags

At half-mast.

– GBM

At the Gates of Mosfilm, 1993

In the summer of 1993, when I was in my early 20s and already besotted with Russian culture, I had the good fortune to land a job at Mosfilm Studios in Moscow. The history of the studio had captured my imagination from afar, and each day that summer I felt that ghostly feeling one sometimes gets when inhabiting the present of a place whose past one has dreamed about. Whenever there was time, I liked to roam the studio grounds, or rather hover among them, convincing myself I could hear the talking stones. Here was a heavy building of beige brick, neoclassical, built to Stalin’s tastes, its authority softened by volunteer shrubs sprouting from the rooftop balustrade. Alongside it, a graveyard of rusted out baby-blue studio buses, each grill aged to uniqueness, destroyed in its own special way. There was a traffic light in an alley between soundstages; the lights had been removed; you could look right through it and see the sky. The studio had once been one of the world’s great centers of filmmaking. Now on certain days I could walk from one end of the vast grounds to the other without bumping into anything resembling a shoot. For me, a kid from Las Vegas, there was a strangely familiar air to the place—it felt like the hollowed downtown of an American city after the construction of a suburban mall. And the feeling was apt: Russian film fans had gotten their mall—the miles of roadside kiosks hawking cheap pirated copies of Hollywood films, many of them straight-to-video jobs of which I had never seen or heard. Without its once lavish state support, the studio had no way to compete with such masterworks.

My job was to translate, coach dialogue, and occasionally dig holes on the set of what was at the time Mosfilm’s marquee project—a Russian-Italian-American joint venture.  We were making a Western. Starring an Italian. Filmed chiefly on a military base an hour outside Moscow. Each morning we all came to the studio, boarded one of the less distressed of the picturesque blue buses, and headed for the set. On my first day of work I had taken the Metro to Kiev Station, caught Trolley 34 to the gates of Mosfilm, and showed my documents to the guard. I’d arrived early. I didn’t know who to look for, where to find them, or quite how to explain my presence. I knew the history of the studio, but its present, and my present, were something of a mystery. The guard waved me through. I wandered onto the grounds. And there I did what one does on a film shoot. I waited.

We were making a Western. Starring an Italian. Filmed chiefly on a military base an hour outside Moscow. Each morning we all came to the studio, boarded one of the less distressed of the picturesque blue buses, and headed for the set. On my first day of work I had taken the Metro to Kiev Station, caught Trolley 34 to the gates of Mosfilm, and showed my documents to the guard. I’d arrived early. I didn’t know who to look for, where to find them, or quite how to explain my presence. I knew the history of the studio, but its present, and my present, were something of a mystery. The guard waved me through. I wandered onto the grounds. And there I did what one does on a film shoot. I waited.

I could have kept waiting all day. There, just inside the gate, was a long row of displays encased in scratched and fogged Lucite—posters of the majestic movies of Mosfilm’s past.  Here was Grigorii Chukhrai’s 1959 classic Ballad of a Soldier. Over there—Mikhail Kalatozov’s 1957 masterpiece The Cranes Are Flying. Eight-thousand miles and eleven time zones from home, I found myself longing for a lost time and place, but it was not a time or place in which I or any of my ancestors had ever lived. In the third year of the bewildering Muscovite 90s, in the heart of the world’s first attempt at a post-Socialist society, I found myself missing a Russia where the chocolate came not from M & M Mars but from the Red October Chocolate Factory, where the soundtrack of the times emitted from the voice box of Vladimir Vysotsky rather than the synthesizers of a Scandinavian globo-pop outfit called Ace of Base, and where the Shock Worker movie theatre on the embankment of the Moscow River was showing The Cranes Are Flying. This fantastic daydream made no sense: I had studied the Soviet century, its deprivations, its brutalities both grandiose and audaciously petty. I could not possibly “miss” the Soviet Union. And yet, on that day, in that peculiar way, what could I say but that I missed the place? Continue: Read the full introduction to “Reentry Shock.” (The essay picks up from here on page four.)

Here was Grigorii Chukhrai’s 1959 classic Ballad of a Soldier. Over there—Mikhail Kalatozov’s 1957 masterpiece The Cranes Are Flying. Eight-thousand miles and eleven time zones from home, I found myself longing for a lost time and place, but it was not a time or place in which I or any of my ancestors had ever lived. In the third year of the bewildering Muscovite 90s, in the heart of the world’s first attempt at a post-Socialist society, I found myself missing a Russia where the chocolate came not from M & M Mars but from the Red October Chocolate Factory, where the soundtrack of the times emitted from the voice box of Vladimir Vysotsky rather than the synthesizers of a Scandinavian globo-pop outfit called Ace of Base, and where the Shock Worker movie theatre on the embankment of the Moscow River was showing The Cranes Are Flying. This fantastic daydream made no sense: I had studied the Soviet century, its deprivations, its brutalities both grandiose and audaciously petty. I could not possibly “miss” the Soviet Union. And yet, on that day, in that peculiar way, what could I say but that I missed the place? Continue: Read the full introduction to “Reentry Shock.” (The essay picks up from here on page four.)

That’s me, back then. Had fun. Time flew.